Discuss current British regulation of aesthetic medicine and how will these two reports affect the future of aesthetic medicine in the United Kingdom?

Dr MJ Rowland-Warmann BSc BDS MSc Aes.Med. PGDip Endod. MJDF RCS (Eng)

For her MSc Masters Degree in Aesthetic Medicine for the Queen Mary University of London. The following essay received a Distinction – the highest mark awarded.

This is an academic essay. If you are a patient seeking treatment from one of Liverpool’s most learned aestheticians then take a look at our main treatment pages here:

Lip fillers Liverpool | Botox Liverpool | Cheek Fillers | Lip fillers gone wrong

This article is a few years old and there are recent exciting developments in the field of regulation in aesthetic medicine. Take a look here at the new 2023 aesthetics licensing proposals.

The cosmetic industry is worth around £3.6 billion and rapidly expanding, both for surgical and non-surgical interventions. Non-surgical interventions now account for 9 out of 10 cosmetic procedures and are lightly-regulated, not classifying as a regulated activity by the CQC (1).

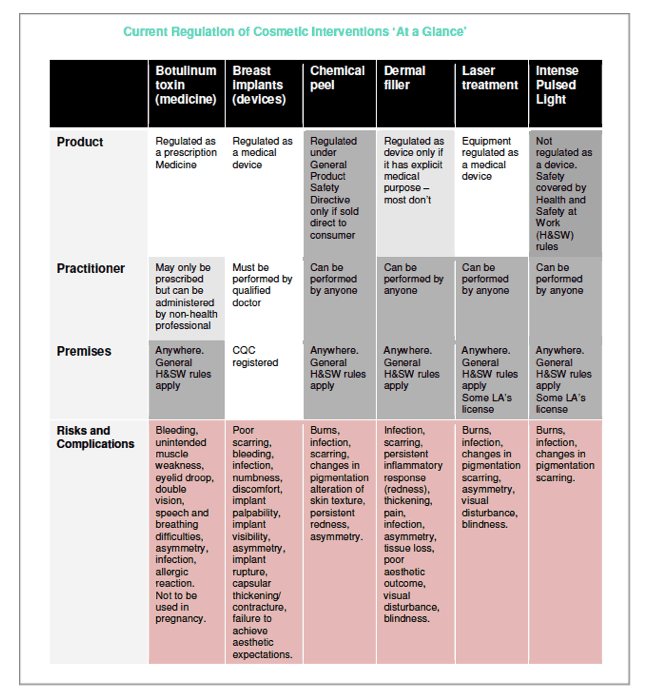

The HEE and Keogh reports into non-surgical cosmetic practice found that in 5 key areas, namely Botulinum toxin, dermal fillers, chemical peels, laser and IPL there is almost no regulation, leaving patients vulnerable, but also that there has been varying standards of care in key elements such as practitioner competence, consenting and complication management in cosmetic surgery (1,2). Reform has been suggested. Public opinion is that non-surgical procedures must be less dangerous, but serious complications can occur in either, and current legislation is not protecting patients effectively, being based largely on guidance rather than concrete regulation (1).

Interventions in the UK

The classification of cosmetic interventions in the UK is as follows:

Level 1a – invasive; may require an overnight stay in a hospital.

Level 1b – invasive; may only require local anaesthetic and should be treated in appropriate outpatient facilities.

It is considered that level 1 carry the most risk and patients should be subject to psychological evaluation prior to embarking on them, with a two-stage consenting process.

Level 2: Minimally invasive. Lower risk procedures which are usually not permanent, reversible and may require the use of local anaesthetic. They should still be undertaken in an appropriate outpatient facility. (3)

PIP

The PIP scandal brought to light concerns about how the cosmetic surgery industry is regulated. Approximately 47,000 women in the UK, and 400,000 worldwide, were affected by faulty breast implants with a rupture rate of around 15.9-33.8% (5,8). Post-2000 PIP devices were shown to contain a non-approved industrial-grade silicone (9) and were immediately removed from the market after an MHRA warning (8). However, their low cost meant they were used long after concerns had been voiced some years earlier (8).

Whilst the MHRA did not advise imminent health risks, women in other countries such as Germany, Netherlands and France were advised PIP implants should be removed. This sparked a debate over cost versus care: some UK surgical providers simply changed their company name or refused to offer assistance to patients, loading the burden of cost onto the NHS (9). It is most likely no accident that in the UK, with healthcare free at the point of delivery and a corporate veil to protect CEOs, moral and legal responsibility have been largely evaded with corporate preoccupation with profits acting against patient care.

Device Regulation

Currently, some dermal fillers are exempt fro EU Product Safety Directives as they can be used as part of a professional service and those not claiming a medical purpose are exempt from EU Medical Device Regulations entirely. There are around 190 dermal fillers in the UK market and patients currently rely on the manufacturer’s declaration of safety and the practitioner’s assessment of the product to ensure treatment success. This is clearly dangerous, and it is argued that all cosmetic implants, including dermal fillers, should be reclassified as prescription-only medical devices and subject to CE marking under the EU Medical Device Directive (1).

The 1993 EU Medical Devices Directive and 2002 Domestic UK laws regulate breast implants, including CE marking, the highest level of medical device regulation in the EU carried out by independent test centres (8). Whilst breast implants are high risk devices and must be proven reasonably safe and effective, in comparison to the US, clinical trials have not been required for their use in the UK (9). Device safety is still lacking: CE test centres have varying controls, which is how PIP was able to go undetected for so long. Incidentally, PIP lost its rights to research and trade in the US in 2000 after an FDA inspection of the manufacturing plant found 11 violations of Manufacturing Practice – this saved American women from the impact of faulty devices, yet this information was not shared by US authorities (9,10). More could have been done to protect patients by the global community.

It is not the first time breast implants have been found to be faulty – in 1990 the Meme implant underwent recall, containing polyurethane similar to mattress foam which degraded into carcinogens (9). The similarities to PIP are disturbing.

Current Regulation in Practice

In the eyes of Keogh, “fillers are a crisis waiting to happen” and the outcomes of several reports in the PIP aftermath included assessment of product safety, practitioner training, public information and options for redress as key elements, highlighting them for improvement in safety in cosmetic procedures (1,2,3)

Products and Practitioners

With the exception of Botulinum Toxin which is a POM, non-surgical cosmetic interventions can be performed by anyone, and anyone can set up training courses. There are no guidelines regarding what constitutes adequate training or verification of courses at present. The responsibility is the practitioners to decide whether they are performing safely and to a high standard following training which, itself is of a varied standard and usually short (hours or a day), leaving practitioners ill equipped to deal with adverse events. (1).

Anyone can buy dermal fillers and use them on patients, without any training in anatomy, physiology, complication management or risk awareness (1). Often these practitioners use misleading titles which can further confuse the public, such as “aesthetic therapist”, which mean very little. Non-healthcare providers are endangering the public by practising singularly without support from clinicians.

Currently there is no speciality register for cosmetic surgery, meaning surgeons are often not directly qualified in the cosmetic field. It is expected that a practitioner should act within their competence, which will increase with experience. It is however the luxury of experience that defines competence and the knowledge of when to refer that currently affords this, rather than a set of rules followed by surgical and non-surgical cosmetic practitioners. Many surgical teams do not perform procedures often enough to be competent and some consultations are not carried out by surgeons, inhibiting successful outcomes (4). Regulators have attempted to improve standards by introducing revalidation (GMC) and CPD records (GDC) but the standards set for cosmetic practice are often vague and undefined (1).

Regulation of non-surgical practice has been attempted by government initiatives such as IHAS (Treatments You Can Trust) and companies such as Save Face; they are optional and have contributed little to safety. The nature of this self-regulatory industry means that subscription is low, and it is only those who are already performing at an acceptable level who sign up, not those under performing in all aspects outlined in the Keogh report and who would arguably need it most (1).

Informed public

Consent is a process rather than just a document and patients must be consented adequately in order to consider their options and information available to them. Often patients have little understanding of the procedure, or the product they are being treated with and this makes it very difficult to make an informed choice (1).

Marketing messages are confusing patients. Marketing is rarely honest or responsible, with financial inducements, discounts and time-limited deals being used to coerce patients into treatments, whilst misleading statements about practitioners and clinics and unrealistic claims about surgery outcome are equally reprehensible (3). Many practices advertise prescription-only medicine, which is illegal and may conflict with the health needs of the patient. Compliance with advertising standards is poor, at only 41% (6), and is leaving vulnerable patients exposed to ruthless marketing tactics (6,7). Enforcing advertising guidelines has been reactive, with offenders only occasionally getting a slap on the wrist and legislation being produced in a piecemeal fashion.

Accessible solution and redress

Due to substandard regulation, non-surgical providers are not necessarily bound by offices, do not need complaints procedures, and are ill-equipped for emergencies. For non-healthcare providers, there is no requirement for insurance. Professional bodies require indemnity for registration to protect both patients and practitioners and non-healthcare practitioners seem to fly below the radar (1,7). It is unacceptable to conduct medical procedures at home, such as at Botox parties, which display a total disregard for patient safety in venues that are incompatible with standards set down by any regulator (3).

A key issue is the provision of emergency care – often the provider contracts out of care when things go wrong, letting the NHS foot the bill or simply expecting the patient to carry additional financial responsibility (2,3). NHS hospitals are often site of private interventions in surgery and are used to shoulder the cost when re-admission is necessary (4).

Neither product, practitioner nor premises have a requirement to be proven safe.

The way forward.

A regulatory framework that is realistic, achievable and appropriate is needed. Products must be safe, practitioners have appropriate skills, and treat patients with respect. It is important that expectations of the service users are met, in terms of outcome and the process by which the treatment is conducted, and for there to be continuity of care (1).

Cosmetic surgery should be made a discrete specialty and a regulator that ensures accountability of practitioners for surgical and non-surgical interventions should be established to ensure the necessary knowledge, skills and values of the providers. Standards for cosmetic surgery training and certification be standardised with recognised clinical qualifications as the outcome and be adaptable in an industry that is fast-moving (1,4). This will facilitate creation of a mandatory register with clearly defined entry requirements such as qualification, safety of premises, ethical advertising compliance and competence (1).

Non-healthcare providers conducting medical procedures is subject of much debate. Most clinicians would welcome the withdrawal of privileges from these individuals by means of legislation. However, in the absence of this, non-healthcare providers should be supervised by a clinical professional (1). This should include being professionally accountable and holding an indemnity and a complaints procedure in place; whilst de rigueur for those from a healthcare background, this must be enforced for other providers. A register of indemnified practitioners would further improve patient awareness (1).

Safe premises mean that infection control and patient welfare is of paramount importance in order to be equipped to deal with adverse event management and medical emergencies (1). Whilst already regulating surgical practices, non-surgical providers should be required to register with the CQC and be subject to more stringent regulation.

In line with ethical marketing, time-limited deals and financial inducements should be banned and the advertising of POM should be restricted (1). This is currently frowned upon but not enforced widely enough.

Record keeping improvement is a pillar of the Keogh report, both locally and nationally. Within the practice records should be clear and contemporaneous, and nationally a breast implant registry should be established to measure long term outcomes of device safety to avoid a repeat of PIP. This should extend also for products such as dermal fillers to ensure devices can be monitored and a reporting system with the MHRA established (1).

Conclusion

Legislation has developed in a reactive fashion. Both minor and major interventions are not well regulated and self-regulation has failed due to the diverse nature of the industry and optional compliance, especially in non-surgical practice. Voluntary codes do not regulate unscrupulous practitioners (4). Patients wrongly assume that because they are committing to a medical procedure it must be adequately regulated (1,7).

The Keogh report, HEE document and the RCS Standards for Cosmetic Practice have illustrated grave problems in the way that the cosmetic industry operates. Legislation does not seem to adequately protect the public, especially with regard to non-healthcare providers conducting medical procedures without clear licensing.

The pillars of these reports are Competency, Consent and Complications. Competency is the training and the appropriateness of the service, taking into consideration the practitioner and products. Consent is a process, including the agreement to treat but also the information needed to make this decision. Complication management is essential, both when things go wrong in the immediate and long term, affected by the method of complaint resolution and the level of practitioner indemnity. In a well-functioning responsible practice, these key elements are a matter of routine.

Cosmetic interventions are an evolution of medicine in line with the needs of the patient population. Even though elective, it does not mean that cosmetic medicine needs to be any less regulated and attempts must be made to regulate it for the protection of its users.

There has been repeated failures in protecting patients despite a history of well-documented problems – first Meme, then PIP, and possibly soon to be dermal fillers (9). Regulatory processes have failed patients and the system cannot be fixed without a complete overhaul. There is a discord between device regulation and the regulation of professionals. Without consistent professional standards, product safety improvements and patient care safeguards in a clearly structured manner, the dangers to the public will not be remedied and will have serious consequences.

WC: 2186 excluding references

References

- Keogh B, Halpin T, Kennedy I, Kydd C, Leonard R, Parry V, Pearce S, Vallance-Owen A, Withey S; Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions. Department of Health Publication (2013).

- Bruce C, Jollie C; Review of Qualifications required for delivery of non-surgical cosmetic. Health Education England (2014)

- Shute J, Clarke A, Rumsey N, Veale D, RCN / Cosmetic Surgery Working Party; Professional Standards for Cosmetic Practice. Royal College of Surgeons Publications (2013)

- Goodwin A, Martin I, Shotton H, Kelly K, Mason M; On the face of it: A review of the organisational structures surrounding the practice of cosmetic surgery. NCEPOD (2010)

- Malata CM, Cunniffe NG, Patel NG; A single surgeon’s experience of the PIP breast implant “saga”: indications for surgery and treatment options/ Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (2013)66, e141-e145.

- Rufai SR, Davis CR; Aesthetic surgery and Google: ubiquitous, unregulated and enticing websites for patients considering cosmetic surgery. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (2014)67, 640-643.

- Kearney L, de Blacam C, Clover AJ, Kelly EJ, O’Shaughnessy M, O’Sullivan ST, O’Broin E; Cosmetic Surgical Practice: Are We complying with professional standards? Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2015)39, 449-451

- Berry MG, Stanek JJ; The PIP mammary prosthesis: A product recall study. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (2012)65, 697-704

- Zuckerman D, Booker N, Nagda S; Public Health implications of differences in US and European Union regulatory policies for breast implants. Reproductive Health Matters (2012)20, 102-111

- Smith R, Lunt N, Hanefield J; The implications of PIP are more than just cosmetic. The Lancet (2012)379, 1180-1181